# 3 Trump’s Two Bodies, or ‘Death Will Set You Free’

Trump’s weaponisation of Covid-relief highlights a recurrent tendency in fascist biopolitics: the tendency to turn on itself

by Seán Kennedy and Joseph Valente

At the climax of W.B. Yeats’s late play, Purgatory (1938), an Old Man stabs his son to death with the same knife he used to kill his father. He hopes, thereby, to redeem the family bloodline from contamination, his mother having sired him with a stable-hand. If the pollution can be contained, in the play’s Purgatorial logic, perhaps his mother’s soul can be laid to rest. The Old Man kills his son while sparing himself (on the basis that he is too old to matter). But the play ends — somewhat inevitably — in failure, the ghost of his mother unappeased: ‘Twice a murderer and all for nothing’.

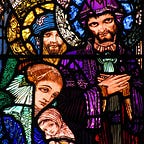

Purgatory is a gruesome enactment of the futility of self-sacrifice as a viable basis for self-regeneration: of the idea, common to both Fascism and Christianity, that death can occasion rebirth. And it is to a moment like this that we might turn in order to understand Trump’s decision to suspend relief negotiations at the height of a pandemic.

But first, what is biopolitics?

Biopolitics is the art of governing the masses at the level of population. It occurs at the intersection of economics and politics, and comprises all those policies and practices that decide who is to be made live (e.g. planned parenthood), or left to die (e.g. covid treatment availability), in the national interest.

It is the process, says Michel Foucault, by which ‘the biological comes under State control’ (2002: 240). When a person with disabilities starves to death because the State denies their benefits; when women are denied reproductive healthcare as a function of race or class; or when checkpoints are deliberately closed to cancer patients, we are in the realm of the biopolitical.

Biopolitics is the production (and elimination) of people on behalf of “the people”. It decides how sick we (the nation) can afford to be, and who must die in order to save us (money). It is an ongoing calculus of disposability trained on “the deserving” and “the undeserving” in pursuit of “national health”. It is intimately linked to fantasies of regeneration: “Make [x] great again”.

By now, it will be clear that Trump’s decision to weaponise Covid relief begs to be understood biopolitically.

Fascist biopolitics, Trump’s biopolitics, is a variant on business as usual that mobilises State resources (including those of inaction) to produce megadeath at the level of the citizenry: ‘immunizing life through the production of death’. At the culmination of Society Must be Defended (2002), Foucault struggled to explain Hitler’s infamous “Nero Decree” in Telegram 71: his order to destroy ‘the means of life’ of the German people (260).

After all, Hitler’s avowed aim throughout the 1930s and 1940s was to regenerate Germany, to revive its fortunes, cleansing it of the parasites and vermin — e.g. the disabled, homosexuals, Jews, the Roma — that had infected it. With the Allies closing in, however, Hitler turned again on his own, dismantling the very infrastructure of the German State. Soon after, of course, he killed himself.

One way to make sense of this is to understand the cult of personality that fascism produces, in which ‘the State’ and ‘the People’ converge in one body: that of the dictator.

Diagnosing that well-known medieval construct, the king’s two bodies, Slavoj Žižek observes how the symbolic mandate of monarchy split the royal frame into a mundane material body, or body natural, subject to the processes of mortality, corruption and reproduction, and a sublime, immaterial body, or body politic, encapsulating the supernal prerogatives of divinely sanctioned rule.

The king could alternatively be of the people, one with them in biological fragility and travail, and beyond the people, partaking of a radically different, empyreal mode of embodiment. It was a legal distinction that allowed one to move against the king (in his body natural) while continuing to revere him (in his body politic): “The king is dead! Long live the king!”

If the king went mad, for example, as with George III, he could be removed from office in his body natural in order to protect him (from himself) in his body politic.

All of this changed in the Age of Revolution (1774–1849). The dethroning of absolute monarchy in Europe, and the concomitant beginnings of liberal democracy, entailed what Claude Lefort (1988) has termed the evacuation of the site of ultimate authority over civil life (39). “The king is dead, long live the people!”

This dramatic shift was marked by the replacement of the division internal to the king’s body with a division of his outward functions among state agents — e.g. monarchical, parliamentary, presidential— each of which bore but one sublunary body, no different in kind to the people they would represent.

This translation — of the dual body of the king into the split body of the nation —would take a distinctive turn in the US. A crucial aspect of the American experiment in self-rule, the so-called “separation of powers”, shivered sovereignty in two, divorcing law from its executive exercise. It was intended as a check on the Royal prerogative, a cautionary response to the King George’s mystical embodiment (even in madness) of divine right — the divine being the transcendent locus where the will and its enactment, the law and its execution, were inseparably at one.

On its face, this Constitutional provision would impede the concentration of controlling authority in any one office or figure, erecting a stay — a structural barrier — against autocratic pretension. But at a deeper, darker level it admits the consolidation, in the president’s person, of symbolic and sovereign roles of governance — head of state and chief executive, the Republican correlative of the king’s two bodies. In so doing, it tempts autocratic pretension, opening the door to a cult of personality that could oe’rleap the structural barrier it fashions.

Donald Trump’s recent bout with Covid-19 — more precisely, his performance of infection, symptomatic distress and vigorous recovery — has revived the spectre of the king’s two bodies as biopolitical strategy: as a warrant for, in Foucault’s terms, ‘making live’ by ‘letting die’.

The public was, at first, treated to Trump’s precarious body natural carted off to Walter Reed hospital in a fevered state. At one point, the would-be dictator even opined he might be “one of the diers,” affecting an intimate knowledge of the Covid affliction, born of the mundane experience of mortality which, as chief executive, he could share with the people. As he improved, however, Trump and Fox news propagandists, like Steve Hilton, re-discovered that second body, the body politic, the recovery of which would signify the recovery of the nation at large.

It is a telling twist on the infamous dictat of Louis XIV: ‘L’état, c’est mon corps’.

Not exactly a sublime immaterial body trailing the glory of the Godhead’s endorsement, this ‘corps’ was propounded as an exceptional body consonant with the exceptionalism of America itself (according to the cherished mythos upon which America’s narcissistic self-conception rests).

It is not incidental to the logic of this position that contracting Covid made Trump feel better than 20 years ago, and was a ‘blessing from God’: it demonstrated his inherent superiority, identifying him as one of “the Elect”. Nor is it accidental that Trump came away from his ordeal committed to the medically debunked but mythically answerable strategy of herd immunity (which he once tellingly confounded with herd mentality).

The takeaway from the balcony speech is that anyone who allows themselves to be ‘dominated’ by the coronavirus is weak, i.e. insufficiently American, and deserves to die anyway. If black Americans are dying at twice the national rate, this merely serves to demonstrate their inherent inferiority. What is being reborn, meanwhile, is the strong America embodied in the resurgent Trump and, by association, his supporters.

Initially, the coronavirus was a hoax. Now Trump is ‘immune’. And if Trump is immune, then other (worthy/fit) Americans should be too. When Trump offered to walk out into the crowd at a recent rally and ‘kiss all the guys’ to prove his immunity, what was at stake, quite literally, was the kiss of death. Ordinary bodies — the sick Trump — must suffer so that a resurgent America — the recovered Trump — might be reborn.

In The Twilight of the Idols (1888), Nietzsche suggested that what does not kill us makes us stronger. The more bizarre implication of Trump’s position is that what does kill us makes us stronger also.

It is a local variation on the recurrent paradox of fascist biopolitics: Americans must die so that America might live.

As if death might liberate America from itself. As if death might make America great again.